Birds of America:Paper Size and Watermarks

In the introduction to her extraordinary work, A Guide to Audubon’s Birds of America, scholar Suzanne M. Low provides a concise and detailed account of the papers used in printing The Birds of America; it is reproduced here in its enterity (more information about Low’s book follows).

Paper Size and Watermarks

The original “double elephant folio” edition of The Birds of America takes its name from the size of the paper. The Oxford English Dictionary defines “elephant” as a size of drawing and cartridge paper 28 x 23 inches and “double elephant” as a similar paper of 40 x 26 ½ inches. (Note that “double elephant” is not twice the size of “elephant”.) The paper [engraver and printer Robert] Havell used was 39 ½ x 26 ½ inches and, while not exactly the double elephant size as defined in the Oxford English Dictionary, it was close enough to be described as such. Audubon, in the prospectus announcing The Birds of America, wrote in the particulars: “The size of the Work will be double Elephant Folio and printed on the finest drawing paper.”

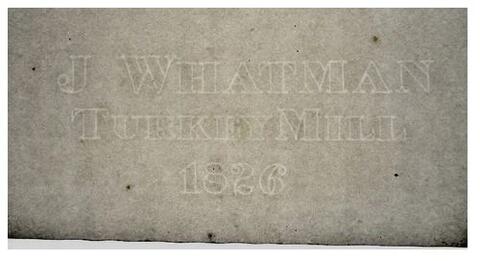

James Whatman was a well-known papermaker in the late 18th century. By Audubon’s time Whatman was gone from the scene. He had sold half of his company, together with the rights to the watermark “J. Whatman / Turkey Mill,” to a family called Hollingsworth, and he had sold the other half with rights to the watermark “J. Whatman” to a man called Balston. The two firms became the leading papermakers and were great rivals. Not only did Havell use their paper for The Birds of America, but Audubon also used it for his paintings.

The paper watermarked “J Whatman / 1827 [to 1838]” is of a heavier weight, with the watermark located a few inches from the edge of the paper. The paper watermarked “J Whatman / Turkey Mill / 1827 [to 1838]” is lighter, with the watermark located closer to the edge of the paper. According to Stephen Massey, former head of Christie’s North American Book Department and an expert who has probably examined more sets of Audubon’s double elephant folio than any present authority, the J. Whatman paper generally retains its whiteness, while the J. Whatman / Turkey Mill paper tends to yellow.

A watermark has a figurative design, while a countermark contains just the name or initials of the papermaker, sometimes with a date. So, strictly speaking, both Whatman papers are countermarked, but it seems simpler here to go with the familiar usage of the term “watermark.”

Prints were pulled from the plates as the orders came in. Thus, one can see prints of the Wild Turkey, Plate I, with watermark dates as early as 1828 and as late as 1834. It is tempting to date the pulling of all prints by the watermark date on the paper, but this may not always be an accurate criterion. Imagine a scene in Havell’s studio in 1832: Havell is pulling prints on paper watermarked 1832. He gets to the bottom of the pile and finds a few sheets of paper left over from 1828, which he then uses. As a general rule, however, the watermark date is a fairly good indication of the date the plate was pulled.

The areas on the paper actually occupied by the plate marks differs. Over eight of the largest and most impressive plates, such as the Osprey, take up almost the entire sheet. Over a third are about 19 x 12 inches, the most common size. The remainder are various sizes between these two, with a few slightly smaller. Some are greater in height than width, and some ate the reverse.

When folios were first broken up and the plates sold separately, the prints were often trimmed down to a suitable border for framing. No one dreamed in those days how valuable Audubons would become, and very little care was taken. Trimming was done carelessly, and legends, plate numbers, and part numbers were often partially or wholly cut off. Often cut off, too, was the watermark, especially in the case of paper watermarked ”J Whatman / Turkey Mill,” where the watermark was closer to the edge of the paper. The print itself in some instances was glued onto cardboard that was not acid-free, with disastrous results. Happily, conservators can rescue many of these, but is of the essence and work should commence immediately.

From: Susanne M. Low, A Guide to Audubon’s Birds of America: A Concordance Containing Current Names of the Birds, Plate Names with Descriptions of Plate Variants, A description of the Bien Edition, and Corresponding Indexes, New Haven: William Reese Co. & Donald A. Heald, 2002. Reproduced with permission of the William Reese Co.

A reccomended related work for further reading: Papermaking and the Art of Watercolor in Eighteenth-Century Britain : Paul Sandby and the Whatman Paper Mill, edited by Theresa Fairbanks Harris and Scott Wilcox, Yale UP, 2006.

Image: The countermark image above is widely reproduced online without attribution or indication of the copy of The Birds of America with which it is associated.