The Lost Birds of Audubon

John James Audubon’s artworks and writings celebrate what today we commonly refer to as biodiversity, the rich and varied forms of life found in a given landscape. For more than a decade, Audubon traveled North America by horse, carriage, steamship, and on foot. He visited and collected specimens from diverse ecosystems in the East, South, and Midwest, recording bird species and the trees, flowers, insects, and other animals that made up their habitats. In his Ornithological Biography, Audubon describes in detail the beauty of old-growth forests, rocky coasts, dense swamps and other American settings; he also documents the abundance of individual bird species—in the case of the Passenger Pigeon he describes flocks so enormous that they completely blocked out the light of the sun when they passed overhead. The lands and lifeforms on the continent experienced dramatic change during the nineteenth century. Forests were cleared for agriculture and industry; creatures considered pests were ruthlessly destroyed while those considered easy food sources were relentlessly hunted. As a result, the American landscape Audubon encountered when he emigrated from France as a young man in 1803 was profoundly different by the time of his death in 1851. Audubon’s work offers opportunities to consider those changes and their lasting consequences. The Beinecke Library’s page openings of The Birds of America in 2019-2020 feature birds that were plentiful during Audubon’s life but that became extinct or were rendered “critically endangered” by the turn of the twentieth century.

Watch video highlights of the Fall 2019 openings here

—

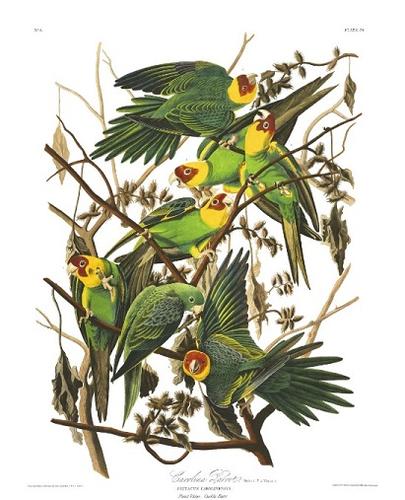

Carolina Parrot (Plate 26)

From Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America, by John James Audubon, 1831–49.

So far from this, the Parakeets are destroyed in great numbers, for whilst busily engaged in plucking off the fruits or tearing the grain from the stacks, the husbandman approaches them with perfect ease, and commits great slaughter among them. All the survivors rise, shriek, fly round about for a few minutes, and again alight on the very place of most imminent danger. The gun is kept at work; eight or ten, or even twenty, are killed at every discharge. The living birds, as if conscious of the death of their companions, sweep over their bodies, screaming as loud as ever, but still return to the stack to be shot at, until so few remain alive, that the farmer does not consider it worth his while to spend more of his ammunition. I have seen several hundreds destroyed in this manner in the course of a few hours, and have procured a basketful of these birds at a few shots, in order to make choice of good specimens for drawing the figures by which this species is represented in the plate now under your consideration. … Our Parakeets are very rapidly diminishing in number; and in some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are now to be seen. … I should think that along the Mississippi there is not now half the number that existed fifteen years ago.

READ Audubon’s complete text at Audubon.org

——————————-

Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Plate 66)

From Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America, by John James Audubon, 1831–49

Travellers of all nations are also fond of possessing the upper part of the head and the bill of the male, and I have frequently remarked, that on a steamboat’s reaching what we call a wooding-place, the strangers were very apt to pay a quarter of a dollar for two or three heads of this Woodpecker. I have seen entire belts of Indian chiefs closely ornamented with the tufts and bills of this species, and have observed that a great value is frequently put upon them. … When wounded and brought to the ground, the Ivory-bill immediately makes for the nearest tree, and ascends it with great rapidity and perseverance, until it reaches the top branches, when it squats and hides, generally with great effect. Whilst ascending, it moves spirally round the tree, utters its loud pait, pait, pait, at almost every hop, but becomes silent the moment it reaches a place where it conceives itself secure. They sometimes cling to the bark with their claws so firmly, as to remain cramped to the spot for several hours after death. When taken by the hand, which is rather a hazardous undertaking, they strike with great violence, and inflict very severe wounds with their bill as well as claws, which are extremely sharp and strong. On such occasions, this bird utters a mournful and very piteous cry.

READ Audubon’s complete text at Audubon.org

—————

Passenger Pigeon (Plate 62)

From Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America, by John James Audubon, 1831–49

The multitudes of Wild Pigeons in our woods are astonishing. … In the autumn of 1813, I left my house at Henderson, on the banks of the Ohio, on my way to Louisville. In passing over the Barrens a few miles beyond Hardensburgh, I observed the Pigeons flying from north-east to south-west, in greater numbers than I thought I had ever seen them before… . The air was literally filled with Pigeons; the light of noon-day was obscured as by an eclipse, the dung fell in spots, not unlike melting flakes of snow; and the continued buzz of wings had a tendency to lull my senses to repose. … Before sunset I reached Louisville, distant from Hardensburgh fifty-five miles. The Pigeons were still passing in undiminished numbers, and continued to do so for three days in succession. The people were all in arms. The banks of the Ohio were crowded with men and boys, incessantly shooting at the pilgrims, which there flew lower as they passed the river. Multitudes were thus destroyed. For a week or more, the population fed on no other flesh than that of Pigeons, and talked of nothing but Pigeons.

READ Audubon’s complete text at Audubon.org

—–